EDGE Curriculum Generative Design PDF

Let’s revisit the car wheel design problem once more. By now, you should be well acquainted with the objectives and constraints of this design challenge. Given the significant advancements in technology, are there any approaches that can automate the design process? In other words, can we obtain computer-generated designs by specifying the design objectives and constraints? The answer is yes. There exist methods known as Generative Design (GD) methods that can accomplish precisely that.

GD is a design paradigm in which computer algorithms computationally consider human-defined objectives, parameter ranges, and constraints to generate designs. GD is an exciting and innovative technology that can help designers explore new possibilities and optimize their designs. GD originated in the 1970s when computers were used for complex design challenges such as shipbuilding and architecture. GD was first used commercially in the manufacturing industry as there was a demand for more efficient, cost-effective ways to design products. GD has been applied in various fields, such as aerospace, automotive, and biomedical. It has also been used for creating novel forms and structures that are not possible with traditional methods, such as an airplane partition wall that achieves 45% less weight (Source).

Figure 11: An example of how generative AI is used in industry. https://www.airbus.com/en/newsroom/news/2016-03-pioneering-bionic-3d-printing

3.1 GD: Problem Definition

Imagine you are looking for the best car wheel design. You have already defined a parametric schema that describes the number of spokes, the shape of each spoke, etc. You may test a few combinations yourself, but what does it take to have the computer find the best combination(s) for you?

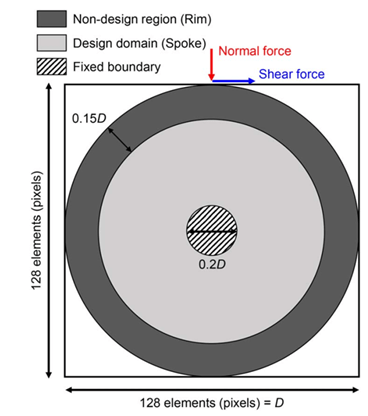

The first step is to tell the computer what “best” means. In generative design, the designer must define the design objectives and constraints not just as vague descriptions, but rather as computable expressions. For example, if your objective is to maximize the stiffness of the car wheel, then you need to input an equation for stiffness. Common objectives may be built into the GD software already, but you still need to choose the right objective(s), or you may end up with wheels that are very strong, but not very stiff.

Figure 12: Example of the Problem Definition for car wheel design in GD. The figure sketches the design domain and boundary conditions, which serve as the design constraints. The objective can be set to maximize the stiffness of the car wheel.

Practice Problem 3.1: Generative Solar Farm Design

Click here to view this practice example.

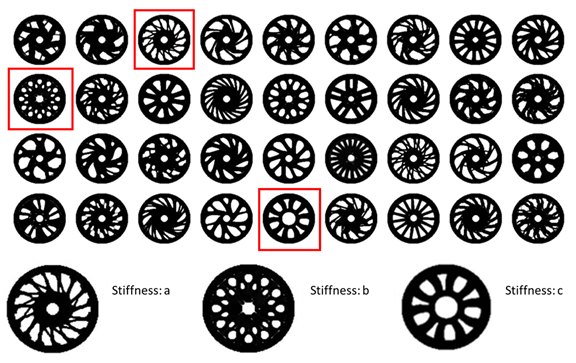

3.2 GD: Exploration

Given the explicitly defined constraints and objectives as input, the GD method can now automatically generate a large number of design options. The designer could review the generated solutions and select the most promising options for further exploration. They could use visualization and analysis tools to understand the performance and behavior of each solution. For example, in the car wheel design problem, there are three designs highlighted in the figure below that the designer finds appealing. Human preferences are essential for assessing and choosing designs in situations where non-engineering factors (e.g., the design’s aesthetics) are critical. These designs can be chosen for further evaluation, including an assessment of their engineering performance (i.e., the stiffness of the car wheel), which has been calculated during the generative design process.

Figure 13: Example of Design Exploration of car wheels in GD. Numerous design options can be automatically generated along with the engineering performance. Comparison of designs can be made in terms of the shapes and stiffness.

Practice Problem 3.2: Generative Solar Farm Design

Click here to view this practice example.

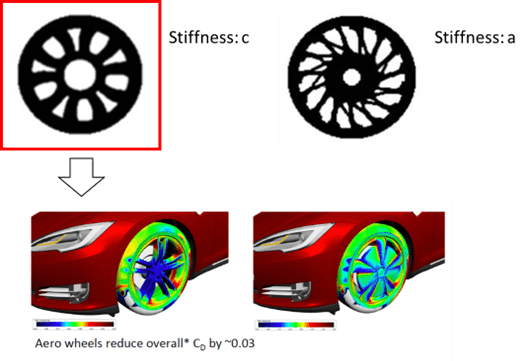

3.3 GD: Evaluation

As mentioned earlier, the engineering performance, which serves as the objective in the generative design process, is typically provided alongside the generated designs. In the case of the car wheel design problem, stiffness is a crucial performance metric, but other factors like aerodynamic performance are also significant. Designers can choose their preferred designs and carry out additional performance evaluations accordingly.

Figure 14: Example of Design Evaluation of car wheels in GD. Besides the stiffness available along with the designs, further engineering performance evaluation (e.g., aerodynamic performance evaluation) can be performed.

Practice Problem 3.3: Generative Solar Farm Design

Click here to view this practice example.

3.4 GD: Iteration

Based on the evaluation, the designer could iterate on the solution by adjusting the inputs and algorithms. The GD method could then generate a new set of solutions based on the updated inputs, and the design process could continue until a satisfactory solution is reached. Through a series of iterations, designers iterate between the design exploration and evaluation stages (sometimes even go back to the problem definition stage), continually refining and enhancing the concepts until they reach the optimal design. The optimal design is the one that best addresses the problem, satisfies user needs, and meets the desired objectives while considering constraints such as cost, manufacturability, and aesthetics. This iterative process allows for continuous improvement, ensuring that the final design is well-considered, effective, and meets the desired goals.

Figure 15: Example of Design Iteration of car wheels in GD. The key role of the designer is to incorporate feedback and insights from testing and evaluation and fine-tune the objectives and constraints for further design exploration. By repeating the process and making adjustments to address any issues, a satisfactory solution can be reached.

Practice Problem 3.4: Generative Solar Farm Design

Click here to view this practice example.

Navigation

Next: Open-Ended Design Problem / Return to table of contents