Table of Contents

Learning Goals

Students will learn:

- Learning Goal 1: About the engineering design process, three design paradigms (traditional, parametric, and generative design) for approaching the engineering design process, and how these paradigms are related (design evolution). Curriculum Section(s): Preface.

- Learning Goal 2: How the design paradigms influence designer behavior throughout the engineering design process (design direction). Curriculum Section(s): Traditional Design.

- Learning Goal 3: About the role of the designer in the traditional design process, throughout four stages: Problem Definition, Exploration, Evaluation, and Iteration. Curriculum Section(s): Traditional Design.

- Learning Goal 4: About the role of the designer in the parametric design process, throughout the same four stages, and how this differs from the traditional design process. Curriculum Section(s): Parametric Design.

- Learning Goal 5: About the role of the designer in the generative design process, throughout the same four stages, and how this differs from the traditional and parametric design processes. Curriculum Section(s): Generative Design.

Concepts

Terms

Preface

Learning Goal 1

Design Process

- Definition: “the complex and iterative set of steps taken by the designer to create an object or experience that solves a problem or meets a goal.”

- Example(s):

- Bridge: “Problems often have specific goals and ways of objectively measuring performance. For example, consider a common real-world engineering design problem: traveling across bodies of water. Cities are often built along the edge of water, leaving the local economy and community dependent on access to consistent and safe travel across the water. This gives the designer a clear goal: to design a structure that allows travel across the water with minimal risk and inconvenience. A common solution is to build a bridge (often a series of bridges) to allow safe and easy travel. However, there are many external constraints to consider. For example, natural water formations and existing infrastructure place strict constraints on bridge location, length, and width. Once the design process is complete, bridge safety and usage can be objectively measured to show how well the solution achieved the goals. The designer must also consider aesthetics, but reliability, cost, and efficiency are often the most important considerations.”

- vs. Art: “The focus on objective measurements of solutions to real-world problems makes the design process unique from similar activities, such as art. The artist has very few, if any, objective requirements. In other words, there are often no “rights” or “wrongs” when creating art. Where a designer may focus on objective requirements and external constraints, an artist’s greatest drive is often to communicate ideas or themes that they feel are important to themselves or a broader audience. The artist must deal with external constraints, such as canvas size or material cost. However, when compared to design, art places a higher emphasis on internal, subjective constraints.”

- “Design often has clear goals to achieve and objective ways of measuring performance. A bridge’s goal is to allow travel across a body of water, and performance can be measured via weight limits and safety records.”

- “The goal of many art projects is to express emotions, themes, and ideas that are important – even if just to the artist. This is often seen through the unique style developed by many street artists.”

- Practice Activities: None.

Design Paradigm

- Definition: “A design paradigm is a framework that provides a foundation for understanding and approaching the design process. Paradigms guide how the designer thinks and acts throughout the design process, and different paradigms may offer vastly different solutions to the same design problem.”

- Example(s): Traditional design, parametric design, and generative design (see concepts below)

- Practice Activities: None

Traditional Design (TD)

- Definition: “[TD] follows established practices and emphasizes human cognition and action. It often involves manual sketching, prototyping, and iterative refinement. To meet predefined requirements and constraints, the designer must rely heavily on their expertise and intuition.”

Parametric Design (PD)

- Definition: “[PD] uses computational algorithms and parameters to guide the design process. Designers define relationships between variables to computationally generate a corresponding design. This approach is highly flexible and allows the designer to explore multiple design possibilities by changing the parameter relationships. This results in adaptable and optimized solutions.”

Generative Design (GD)

- Definition: “[GD] employs artificial intelligence to algorithmically generate up to thousands of design options for the human designer. Design goals and constraints are defined, and the computer generates and evaluates numerous design iterations automatically. This method often generates unconventional and innovative solutions not typically conceived through traditional design methods.”

Design Evolution

- Definition: “The natural progression from traditional design, to parametric design, and finally to generative design, based on technological development. Each paradigm builds upon the previous one and incorporates computational elements to expand the possibilities for design exploration and optimization. It’s important to note that these paradigms are not mutually exclusive, and designers often use a combination of them.”

- Example(s): Car wheel design

- Practice Activities: None.

Traditional Design (TD)

Learning Goal 2

Students learn: How design paradigms change the way one acts during the design process (design direction).

Traditional Design (TD)

- Definition: “[The TD process includes] the established principles and practices for conducting engineering design. This paradigm emphasizes human activities, such as manual sketching, to explore design possibilities. Traditional design relies on the designer’s expertise, experience, and intuition to generate solutions based on predefined requirements and constraints,”

- Example(s): Design Direction – forward design vs. backward design (see below).

- Practice Activities: None.

Design Space

- Definition: “[The Design Space is] the multidimensional space that represents all possible design options or solutions for a given problem or task. It represents the entire range of potential design configurations, parameters, and variations that can be explored. The design process focuses on exploring and exploiting the design space to search designs that meet the criteria,”

- Example(s):

- Practice Activities: None.

Objective Space

- Definition: “[the Objective Space] represents the performance or evaluation criteria used to assess and compare different designs. It is typically defined by the goals, objectives, or metrics that a design should meet. The objective space provides a framework for evaluating designs based on important criteria and comparing different designs based on their performance,”

- Example(s): “For example, if my goal is to grow a garden, one of the objectives might be to control the amount of water I use, and the metric would be volume of water (Liters/gallons),”

- Practice Activities: None.

Design Direction

- Definition: “A key difference between the design paradigms is in how the designer engages with the Design Space and the Objective Space. … However, since design iterations will occur in both ways of design, the forward and backward directions described are the concepts more emphasized at the level of design thinking or how we mentally approach a design problem from the beginning,”

- Example(s): “Designers using the traditional design paradigm take a different design direction than designers using parametric or generative design paradigms,”

- Practice Activities: None.

Forward Design

- Definition: “[Forward design] occurs when the designer works from the design space to the objective space,”

- Example(s): “Designers begin by extrapolating values for parameters from their previous experience and then examine whether these chosen values align with the desired objectives. TD and PD often follow a forward design direction,”

- Practice Activities: None.

Backward Design

- Definition: “[In Backwards Design,] design moves from the objective space to the design space. ” … “often adopted in GD.”

- Example(s): “Designers start by defining the objectives for generative design software based on the specified criteria and constraints and then use the software to find the values of the parameters that meet the objectives,”

- Practice Activities: None.

Learning Goal 3

Students learn: The roles of the designer in the traditional design process (four stages: Problem Definition, Exploration, Evaluation, and Iteration).

TD: Problem Definition

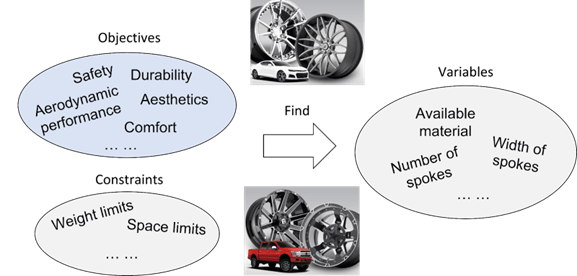

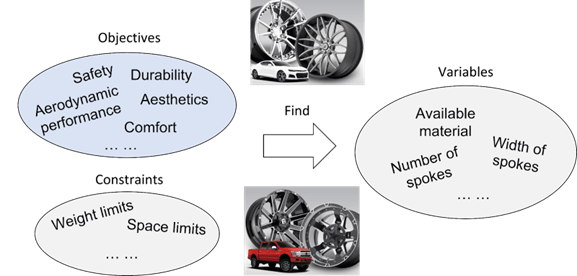

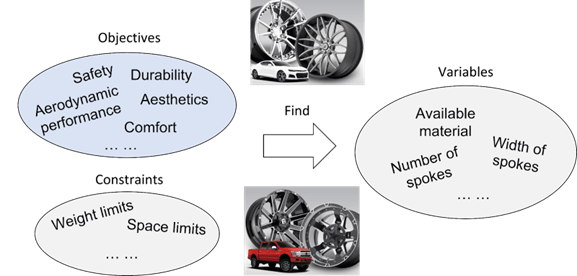

Objectives

- Definition: “The designer starts by understanding the specific problem that the design should solve. This includes clearly defining the objectives to achieve and identifying any constraints that the design must work within.”

- Example(s): “Imagine you are designing the wheels for a new car…Should it be sturdy or lightweight?”

- Practice Activities: Solar Farm Design, Questions 1 and 2.

Constraints

- Definition: “Design objectives are qualities that the customer wants the finished product to possess. In some cases, these objectives are measurable performance criteria. Other design objectives are more subjective.”

- Example(s): For an engineer tasked with designing a new car wheel, possible design objectives include: safety, durability, aerodynamic performance, aesthetics, and comfort. Some of these objectives can be quantified. For example, the customer might state that a “durable” wheel is one with an expected lifespan of at least 300,000 miles. Other objectives cannot be quantified. For example, the customer might state that they want a wheel that “looks cool on my new sports car.”

- Practice Activities: Solar Farm Design, Questions 1 and 2

Variables

- Definition: “Variables are characteristics of the design that are manipulated by the designer as they explore the design space to create a set of potential design solutions..”

- Example(s): “Returning to the car wheel design example, potential variables include the number of spokes, the width of these spokes, and the material(s) that the wheel is made of. The designer can create a theoretically infinite number of design alternatives by changing these and any other relevant variables”

- Practice Activities: Solar Farm Design, Question 1

TD: Exploration

- Definition: “The goal of this stage is to identify how the design variables and constraints are related to the objective(s) by generating different design concepts that may each achieve the objective (Figure 4.). Therefore, exploration often involves two major tasks: 1) the identification of all possible design variables and constraints, and 2) the generation and synthesis of all possible designs in the design space defined by the design variables and constraints.”

- Example(s): “Designers often start by sketching various concepts and ideas. They explore different shapes, patterns, and textures that may enhance the performance or aesthetics of the wheels. Designers [then] translate their conceptual sketches into digital models using computer-aided design (CAD) software, where they can further experiment with different dimensions, materials, and finishes.”

- Practice Examples: Solar Farm Design

Diverge

- Definition: “A common strategy for exploring the design space is to diverge and generate designs that are as different from each other as possible.”

- Example(s): ”For example, two main objectives in car wheel design are wheel strength and wheel speed. First, think about designing a wheel optimized for strength. What are the strongest and most durable materials? How wide should the spokes be? In this case, the designer may choose a heavy material to add strength, and utilize wide spoke width to more equally distribute pressure along the inside of the wheel. Now, imagine you are designing a wheel optimized for speed. How would this be different from the previous wheel? Are lighter materials available? How can aerodynamics be improved? A lighter material will reduce the weight of the vehicle but may sacrifice strength. Exploring the “edges” of the design space will often help the designer understand how these variables impact design performance.”

- Practice Examples: Solar Farm Design

TD: Evaluation

- Definition: “The first goal of the Evaluation stage is to analyze the design performance to determine if the objectives and constraints are satisfied.”

- Example(s): “Some designs will be better than others. But how do you know if aluminum wheels are more durable than steel wheels, or less durable?”

- Practice Examples: Solar Farm Design, Questions 3, 4, and 5

Trade-Off

- Definition: “Each design may perform better at some objectives and worse at others.”

- Example(s): “There may be a trade-off between the strength of a truck wheel and the speed of a race car wheel.”

- Practice Examples: Solar Farm Design, Question 4

Dominated Design

- Definition: “Dominated designs perform worse [than the design alternatives] in all metrics.”

- Example(s): “Imagine a third car wheel design that is both weaker than the truck wheel and slower than the race car wheel.”

- Practice Examples: Solar Farm Design, Questions 6, 7, 8, and 10

Non-Dominated Design

- Definition: “A non-dominated design performs better in at least one objective than every other design.”

- Example(s): “In the previous example, both the truck wheel [which has superior strength] and the race car wheel [which has superior speed] are non-dominated and are worthy candidates.“

- Practice Examples: Solar Farm Design, Questions 6, 7, 8, and 10

Pareto Front

- Definition: “The non-dominated designs form the Pareto Front.”

- Example(s): “In the car wheel design example, the Pareto Front will include one design optimized for durability, one design optimized for safety, one design optimized for comfort, one design optimized for aesthetics, and so on for each specified design objective.”

- Practice Examples: Solar Farm Design, Questions 6, 7, 8, and 10

TD: Iteration

- Definition: “The goal of Iteration is to refine the designs to eventually achieve the goal(s). This can be achieved in several manners. For example, a designer can evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of different ideas by optimizing alternative concepts and comparing them against each other. This builds a deeper understanding of the design space and the objective space for the designer to consider as they work to refine dominated designs into non-dominated designs by modifying variables based on previous evaluation. ”

- Example(s): Figure 6

- Practice Examples: Solar Farm Design, Question 9

Design of Experiments

- Definition: “Designers can use design of Experiments (DOE) to change one variable at a time and evaluate the results to determine cause-and-effect relationships.”

- Example(s): “For example, if one of your designs uses 6 spokes, what changes when you use 7 spokes? 8 spokes?”

- Practice Examples: Solar Farm Design, Question 9

Parametric Design (PD)

Learning Goal 4

Parametric Design (PD)

- Definition: “Parametric design (PD) uses algorithms and mathematical equations to create and manipulate digital models. In parametric design, the key parameters of a design, such as size, shape, and orientation, are defined and quantified, and their relationships can be defined by mathematical formulas or rules, rather than by static dimensions or measurements.”

- Example(s): “In the 1980s and 1990s, researchers and practitioners in fields such as architecture, engineering, and product design began to develop new tools and techniques for parametric modeling, which allowed them to create complex and highly customizable designs that could be easily modified and adapted to meet different needs or specifications.”

- Practice Examples: Parametric Solar Farm Design

PD: Problem Definition

Parametric Schema

- Definition: “[In parametric design, designers] also create a parametric schema (Figure 7) that models the relationships between variables”

- Example(s): “[Take, for example, the] parametric design of a car wheel frame in Grasshopper. In addition to identifying the same design variables (e.g., number of spokes, width of spokes), the designer also creates a parametric model / schema that models the relationships between variables.”…“For an example, let’s return to the car wheel design problem. If the weight is an important variable, its mathematical relationship to other variables (e.g., material(s) used, number of spokes, width of the spokes) should be expressed as an equation. Similar equations defining cost and durability might also be necessary. These and all other relevant equations comprise the parametric schema for that design problem.”

- Practice Examples: none

Quantitative and Computable Variables

- Definition: “To achieve this, the designer must define the design variables not just as vague descriptions, but rather as quantitative and computable parameters with specific ranges. In other words, designers must write equations or use computer software to mathematically define the relationships between all relevant variables. Designers must then specify the acceptable range of values for each variable, by providing an upper and lower limit.”

- Example(s): “For an example, let’s return to the car wheel design problem. If the weight is an important variable, its mathematical relationship to other variables (e.g., material(s) used, number of spokes, width of the spokes) should be expressed as an equation. Similar equations defining cost and durability might also be necessary. These and all other relevant equations comprise the parametric schema for that design problem.”

- Practice Examples: Parametric Solar Farm Design, Questions 1 and 2

PD: Exploration

- Definition: “In this stage, designers use parametric modeling tools (Figure 8a) to generate and evaluate multiple design options or alternatives (Figure 8b). This may involve creating digital prototypes, testing different combinations of design parameters, and exploring different scenarios or use cases.”

- Example(s): “As a designer, having 2-3 designs is great, but having 20-30 designs is even better. For example, what if you want to compare designs with not just 6 spokes, but also 7, 8, … 20 spokes?”

- Practice Examples: Parametric Solar Farm Design, Questions 3 and 4

PD: Evaluation

- Definition: “Designers evaluate the performance, feasibility, and suitability of the design options that were generated in the exploration stage. However, with the ability to create dozens (if not hundreds) of designs quickly in PD, designers can now evaluate and compare more designs, increasing their chance of finding the optimal design solution or important information that can be used in future iterations.”

- Example(s): None.

- Practice Examples: Parametric Solar Farm Design, Questions 5-8

PD: Iteration

- Definition: “In this stage, designers refine and improve the selected designs by adjusting design parameters (Figure 9) through a series of iterative steps. This may involve incorporating feedback and insights from testing and evaluation into the design, making adjustments or modifications to address any issues or concerns, and then repeating the process until a satisfactory solution is reached. The goal is to create a final design that meets all of the project requirements and that has been optimized for performance, efficiency, and user experience.”

- Example(s): “Imagine you have evaluated your car wheel design and want to make a couple changes. Maybe you want to add 2 spokes, reduce their width by 5%, and switch to a different material. Would you start from scratch, or would you rather change some numbers and drag some sliders?”

- Practice Examples: Parametric Solar Farm Design, Questions 9-13

Generative Design (GD)

Learning Goal 5

Generative Design (GD)

- Definition: “Are there any approaches that can automate the design process? In other words, can we obtain computer-generated designs by specifying the design objectives and constraints? The answer is yes. There exist methods known as Generative Design (GD) methods that can accomplish precisely that…GD is a design paradigm in which computer algorithms computationally consider human-defined objectives, parameter ranges, and constraints to generate designs.”

- Example(s): “GD has been applied in various fields, such as aerospace, automotive, and biomedical. It has also been used for creating novel forms and structures that are not possible with traditional methods, such as an airplane partition wall that achieves 45% less weight.”

- Practice Examples: None.

GD: Problem Definition

- Definition: “In generative design, the designer must define the design objectives and constraints not just as vague descriptions, but rather as computable expressions.” pg. 44.

- Example(s): “For example, if your objective is to maximize the stiffness of the car wheel, then you need to input an equation for stiffness. Common objectives may be built into the GD software already, but you still need to choose the right objective(s), or you may end up with wheels that are very strong, but not very stiff.” pg. 44.

- Practice Examples: Generative Solar Farm Design, Question 1, pg. 45.

GD: Exploration

- Definition: “Given the explicitly defined constraints and objectives as input, the GD method can now automatically generate a large number of design options.” pg. 46.

- Example(s): “For example, in the car wheel design problem, there are three designs highlighted in the figure below that the designer finds appealing. Human preferences are essential for assessing and choosing designs in situations where non-objective factors (e.g., the design’s aesthetics) are critical. These designs can be chosen for further evaluation, including an assessment of their engineering performance (i.e., the stiffness of the car wheel), which has been calculated during the generative design process.” pg. 46.

- Practice Examples: Generative Solar Farm Design, Questions 1-3, pgs. 48-49.

GD: Evaluation

- Definition: “[The designer can] use visualization and analysis tools to understand the performance and behavior of each solution…Human preferences are essential for assessing and choosing designs in situations where non-engineering factors (e.g., the design’s aesthetics) are critical.” pg. 46.

- Example(s): “In the case of the car wheel design problem, stiffness is a crucial performance metric, but other factors like aerodynamic performance are also significant. Designers can choose their preferred designs and carry out additional performance evaluations accordingly.” pg. 50.

- Practice Examples: Generative Solar Farm Design, Questions 4-10, pgs. 51-52.

GD: Iteration

- Definition: “Based on the evaluation, the designer could iterate on the solution by adjusting the inputs and algorithms. The GD method could then generate a new set of solutions based on the updated inputs, and the design process could continue until a satisfactory solution is reached. Through a series of iterations, designers iterate between the design exploration and evaluation stages (sometimes even go back to the problem definition stage), continually refining and enhancing the concepts until they reach the optimal design.” pg. 53.

- Example(s): “Figure 15: Example of Design Iteration of car wheels in GD. The key role of the designer is to incorporate feedback and insights from testing and evaluation and finetune the objectives and constraints for further design exploration. By repeating the process and making adjustments to address any issues, a satisfactory solution can be reached.” pg. 53.

- Practice Examples: Generative Solar Farm Design, Questions 11-15, pgs. 54-55.