Design Makes Us Human

Why is design important? Everything artificial was designed by a human – The effects of design shape our day-to-day lives. Design is what sets us apart from other life on Earth. Non-human animals can communicate, build modest structures and alter their environments. Some are intelligent and curious, exploring their surroundings and even passing down traditions to their young. However, humans explore and interact with the environment in a way that is unique to our species – we design ways to do things that have never been done. Humans explore unknown spaces without knowing what lies ahead. We are the only species to search the ocean for new land, and upon finding it, invent new ways of changing it. Looking towards the future, humans are the only species from Earth with the potential to inhabit other planets.

Our obsession with novelty and progress has not been without consequences. History has seen a long series of successful (and failed) experiments that were necessary to design the complex ways that we live our lives. But while an elephant may be able to remember its way home during rush hour, there are no elephant cities from which to drive home. No team of beavers could reconstruct the Hoover Dam, nor could a parrot improve the writings of Leo Tolstoy. Cities, dams, and the culture-rich worlds that we inhabit have only been designed by humans. Through thoughtful planning and deliberate action, design lets us adapt our surroundings to suit our lifestyles and make tools to change how we live. Design is what makes us human.

What Is Design, and How Is It Different from Other Activities, Like Art?

Design can change our world in many ways. Thus, design can mean many different things across a wide range of contexts. Here, we focus on the design process, the complex and iterative set of steps taken by the designer to create an object or experience that solves a problem or meets a goal. Problems often have specific goals and ways of objectively measuring performance. For example, consider a common real-world engineering design problem: traveling across bodies of water. Cities are often built along the edge of water, leaving the local economy and community dependent on access to consistent and safe travel across the water. This gives the designer a clear goal: to design a structure that allows travel across the water with minimal risk and inconvenience. A common solution is to build a bridge (often a series of bridges) to allow safe and easy travel. However, there are many external constraints to consider. For example, natural water formations and existing infrastructure place strict constraints on bridge location, length, and width. Once the design process is complete, bridge safety and usage can be objectively measured to show how well the solution achieved the goals. The designer must also consider aesthetics, but reliability, cost, and efficiency are often the most important considerations.

The focus on objective measurements of solutions to real-world problems makes the design process unique from similar activities, such as art. The artist has very few, if any, objective requirements. In other words, there are often no “rights” or “wrongs” when creating art. Where a designer may focus on objective requirements and external constraints, an artist’s greatest drive is often to communicate ideas or themes that they feel are important to themselves or a broader audience. The artist must deal with external constraints, such as canvas size or material cost. However, when compared to design, art places a higher emphasis on internal, subjective constraints.

Left: Design often has clear goals to achieve and objective ways of measuring performance. A bridge’s goal is to allow travel across a body of water, and performance can be measured via weight limits and safety records. Right: The goal of many art projects is to express emotions, themes, and ideas that are important – even if just to the artist. This is often seen through the unique style developed by many street artists.

What Are the Different Ways to Design?

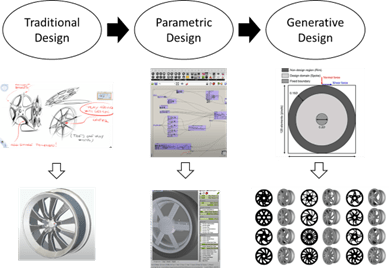

There are many different ways to accomplish a goal, and design is no exception. Paradigms (Greek; loosely translated as pattern) are collections of ideas that shape the way we think and act. A design paradigm is a framework that provides a foundation for understanding and approaching the design process. Paradigms guide how the designer thinks and acts throughout the design process, and different paradigms may offer vastly different solutions to the same design problem. There are three major paradigms to engineering design: Traditional, Parametric, and Generative.

- Traditional design (TD) follows established practices and emphasizes human cognition and action. It often involves manual sketching, prototyping, and iterative refinement. To meet predefined requirements and constraints, the designer must rely heavily on their expertise and intuition.

- Parametric design (PD) uses computational algorithms and parameters to guide the design process. Designers define relationships between variables to computationally generate a corresponding design. This approach is highly flexible and allows the designer to explore multiple design possibilities by changing the parameter relationships. This results in adaptable and optimized solutions.

- Generative design (GD) employs artificial intelligence to algorithmically generate up to thousands of design options for the human designer. Design goals and constraints are defined, and the computer generates and evaluates numerous design iterations automatically. This method often generates unconventional and innovative solutions not typically conceived through traditional design methods.

The relationship between these paradigms can be seen as a progression from traditional design, to parametric design, and finally to generative design, as shown in the figure on the right. Such a progression is a natural outcome of science and technology development. Each paradigm builds upon the previous one and incorporates computational elements to expand the possibilities for design exploration and optimization. However, it’s important to note that these paradigms are not mutually exclusive, and designers often use a combination of them. We will focus on each of these paradigms in depth, starting with Traditional Design.