EDGE Curriculum Traditional Design PDF

We will first focus on Traditional Design: the established principles and practices for manually conducting engineering design. This paradigm emphasizes human activities, such as manual sketching, to explore design possibilities. Traditional design relies on the designer’s expertise, experience, and intuition to generate solutions based on predefined requirements and constraints. A key difference between the design paradigms is in how the designer engages with the Design Space and the Objective Space.

The Design and Objective Spaces

The Design Space is the multidimensional space that represents all possible design options or solutions for a given problem or task. It represents the entire range of potential design configurations, parameters, and variations that can be explored. The design process focuses on exploring and exploiting the design space to search designs that meet the criteria.

The Objective Space represents the performance or evaluation criteria used to assess and compare different designs. It is typically defined by the goals, objectives, or metrics that a design should meet. For example, if my goal is to grow a garden, one of the objectives might be to control the amount of water I use, and the metric would be volume of water (Liters/gallons). The objective space provides a framework for evaluating designs based on important criteria and comparing different designs based on their performance in these criteria.

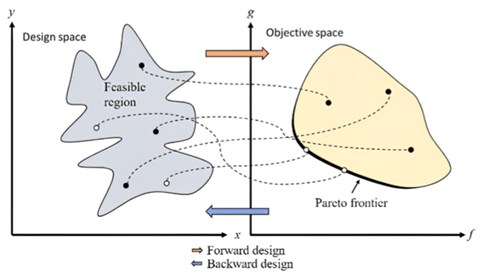

Designers using the traditional and parametric design paradigms take a different design direction than designers using generative design. As shown in Figure 1, Forward Design occurs when the designer works from the design space to the objective space. Designers begin by extrapolating values for parameters from their previous experience and then examine whether these chosen values align with the desired objectives. TD and PD often follow a forward design direction.

This is different from Backward Design, which is often adopted in GD. In backward design, design moves from the objective space to the design space. Designers generally begin by defining the objectives for generative design software based on the specified criteria and constraints and then use the software to find the values of the parameters that meet the objectives. However, forward and backward design are general approaches to the early design phases as later stage iteration will occur in both directions.

1.1 TD: Problem Definition

Imagine you are designing the wheels for a new car. Think about the first step you would take – Would you immediately start sketching your sleek and creative ideas, or ask the client what style they want?

Figure 2. Now imagine that you have designed a sturdy and heavy truck wheel (left), only to realize that your client wanted a sports car (right)!

The beginning of the design process requires the designer to understand the specific problem that the design solution should solve. This includes clearly defining the objectives to achieve and identifying any constraints that the design must work within. For example, a designer would ask: Should the car wheel be sturdy or lightweight? How much is the budget?

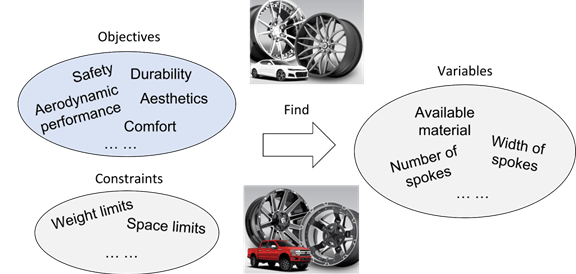

Design objectives are qualities that the client wants the finished product to possess. In some cases, these objectives are measurable performance criteria. Other design objectives may be more subjective. For an engineer tasked with designing a new car wheel, possible design objectives include safety, durability, aerodynamic performance, aesthetics, and comfort. Some of these objectives can be quantified, e.g., wheel durability can be measured in miles, and a client may request a minimum lifespan of 300,000 miles. Other objectives, like aesthetics, cannot be quantified. If a client states that they want a wheel that “looks cool on my new sports car,” the designer is required to make subjective judgements on the design aesthetics.

Design constraints are limiting criteria that restrict the possible range of designs. Constraints may be imposed by a wide range of factors, including performance, cost, safety, environmental regulations, or other considerations. Their impact is to limit the designer to work within certain regions of the design space. Designs that fall outside this region, i.e., violate the constraints, will be unacceptable to the client or problem context. For example, weight and space are key constraints in car wheel design. The client may place constraints on the weight limit (e.g., 65 lbs.), wheel diameter (e.g., 20 in.), and/or the wheel width (e.g., 9 in.).

Defining the objectives and constraints often begins by talking to the client, but this may not always be helpful. In some cases, the client is unaware of the underlying problem that needs to be solved and may only be able to communicate the symptoms of the problem (e.g., “The current wheel is too heavy,” or “The wheel is ugly”). This would require the designer to closely analyze the problem to deduce the underlying key variables and constraints (Figure 3).

Variables are characteristics of the design that are manipulated by the designer as they explore the design space to create a set of potential design solutions. Returning the car wheel design example, potential variables include the number of spokes, the width of these spokes, and the material(s) that the wheel is made of. The designer can create a theoretically infinite number of design alternatives by changing these and any other relevant variables.

Recognizing the key design variables and constraints allows the designer to define the design space, which contains all possible design solutions. For example, one possible solution is aluminum wheels with five spokes; another solution may be steel wheels with six spokes. Next, we will go through a practice example to experience these ideas at work.

Next, we will go through a practice example to experience these ideas at work.

Practice Example 1.1: Solar Farm Design

Click here to view this practice example.

1.2 TD: Exploration

We will continue with our car wheel example. Imagine that you have decided that material and spoke width are two important variables of your car wheel design. So, how do you decide whether to use wide aluminum spokes, or thin steel spokes?

Once you have defined the design space and considered how different variables may affect performance, you can enter the next stage – Exploration. The goal of this stage is to identify how the design variables and constraints are related to the objective(s) by generating different design concepts that may each achieve the objective (Figure 4.). Therefore, exploration often involves two major tasks: 1) the identification of all possible design variables and constraints, and 2) the generation and synthesis of potential design solutions in the design space defined by the design variables and constraints.

A common strategy for exploring the design space is to diverge and generate designs that are as different from each other as possible. For example, two main objectives in car wheel design are wheel strength and wheel speed. First, think about designing a wheel optimized for strength. What are the strongest and most durable materials? How wide should the spokes be? In this case, the designer may choose a heavy material to add strength, and utilize wide spoke width to more equally distribute pressure along the inside of the wheel.

Now, imagine you are designing a wheel optimized for speed. How would this be different from the previous wheel? Are lighter materials available? How can aerodynamics be improved? A lighter material will reduce the weight of the vehicle but may sacrifice strength. Exploring the “edges” of the design space will often help the designer understand how these variables impact design performance.

Figure 4. Exploration in car wheel design. Left, Designers often start by sketching various concepts and ideas. They explore different shapes, patterns, and textures that may enhance the performance or aesthetics of the wheels. Right, Designers translate their conceptual sketches into digital models using computer-aided design (CAD) software, where they can further experiment with different dimensions, materials, and finishes.

Practice Example 1.2: Solar Farm Design

Click here to view this practice example.

1.3 TD: Evaluation

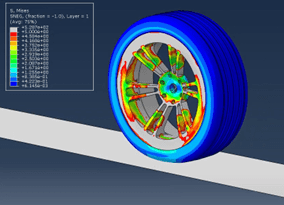

Some designs will be better than others. But how do you know if aluminum wheels are more durable than steel wheels, or less durable? The first goal of the Evaluation stage is to analyze the design performance to determine if the objectives and constraints are satisfied (Figure 5a). Here is where things get tricky: Each design may perform better at some objectives and worse at others. There may be a trade-off between the strength of a truck wheel and the speed of a race car wheel. How do designers choose between competing options?

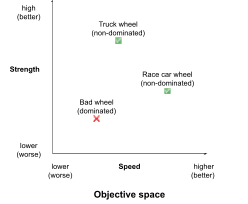

Designs may either be dominated by other designs or non-dominated (Figure 5b).

Dominated designs perform worse in all metrics.

Imagine a third car wheel design that is both weaker than the truck wheel and slower than the race car wheel.

A non-dominated design performs better in at least one objective than every other design.

In the previous example, both the truck wheel and the race car wheel are non-dominated and are worthy candidates. The second goal of Evaluation is to identify the non-dominated designs and remove dominated designs. The remaining non-dominated designs form the Pareto Front. In the car wheel design example, the Pareto Front will include one design optimized for durability, one design optimized for safety, one design optimized for comfort, one design optimized for aesthetics, and so on for each specified design objective.

Figure 5. (a) Evaluation of a car wheel design using computer-aided engineering (CAE) software. (b) A comparison of three car wheel designs in the objective space.

Some goals can be objectively measured, like the safety, durability, and aerodynamic performance of a car wheel, often with the help of computer-aided engineering (CAE) software. However, subjective goals like aesthetics, beauty, and creativity cannot be easily coded into a computer model. Thus, design aesthetics are often left to the discretion of the human designer, who must balance beauty and performance.

Practice Example 1.3: Solar Farm Design

Click here to view this practice example.

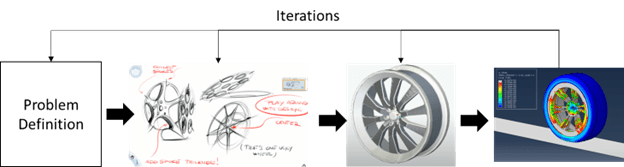

1.4 TD: Iteration

Engineering design is a complex task that often requires the designer to cycle through the design process to refine a concept towards the goals identified earlier. The concepts generated during Exploration, and the insights and comparisons from Evaluation will inform the designer as they continue to solve the problem. The goal of Iteration is to refine the designs to eventually achieve the goal(s). This can be achieved in several manners. For example, a designer can evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of different ideas by optimizing alternative concepts and comparing them against each other. This builds a deeper understanding of the design space and the objective space for the designer to consider as they work to refine dominated designs into non-dominated designs by modifying variables based on previous evaluation.

The goal of Iteration is to move from a dominated design towards a non-dominated design by modifying one or more variables. Ideally, each successive design should improve on the performance of the previous design, according to the specified objective.

The key role of the designer is to incorporate feedback and insights from testing and evaluation into future exploration. By repeating the process and making adjustments to address any issues, a satisfactory solution can be reached. Designers can use Design of Experiments (DOE) to change one variable at a time and evaluate the results to determine cause-and-effect relationships. For example, if one of your designs uses 6 spokes, what changes when you use 7 spokes? 8 spokes?

Figure 6: Iteration in car wheel design. Through a series of iterations, designers cycle between the design exploration, evaluation, and (sometimes) the problem definition stages to continually refine and enhance the concepts until they reach the optimal design. The optimal design is the one that best addresses the problem, satisfies user needs, and meets the desired objectives while considering constraints such as cost, manufacturability, and aesthetics. This iterative process allows for continuous improvement, ensuring that the final design is well-considered, effective, and meets the desired goals.

Practice Example 1.4: Solar Farm Design

Click here to view this practice example.